In the bygone era, a remarkable chapter in history unfolded, centered around the dedicated men known as the icemen.

In the bygone era, a remarkable chapter in history unfolded, centered around the dedicated men known as the icemen.

These individuals embarked on a crucial mission to deliver blocks of ice, playing an indispensable role in a time before the widespread availability of refrigeration

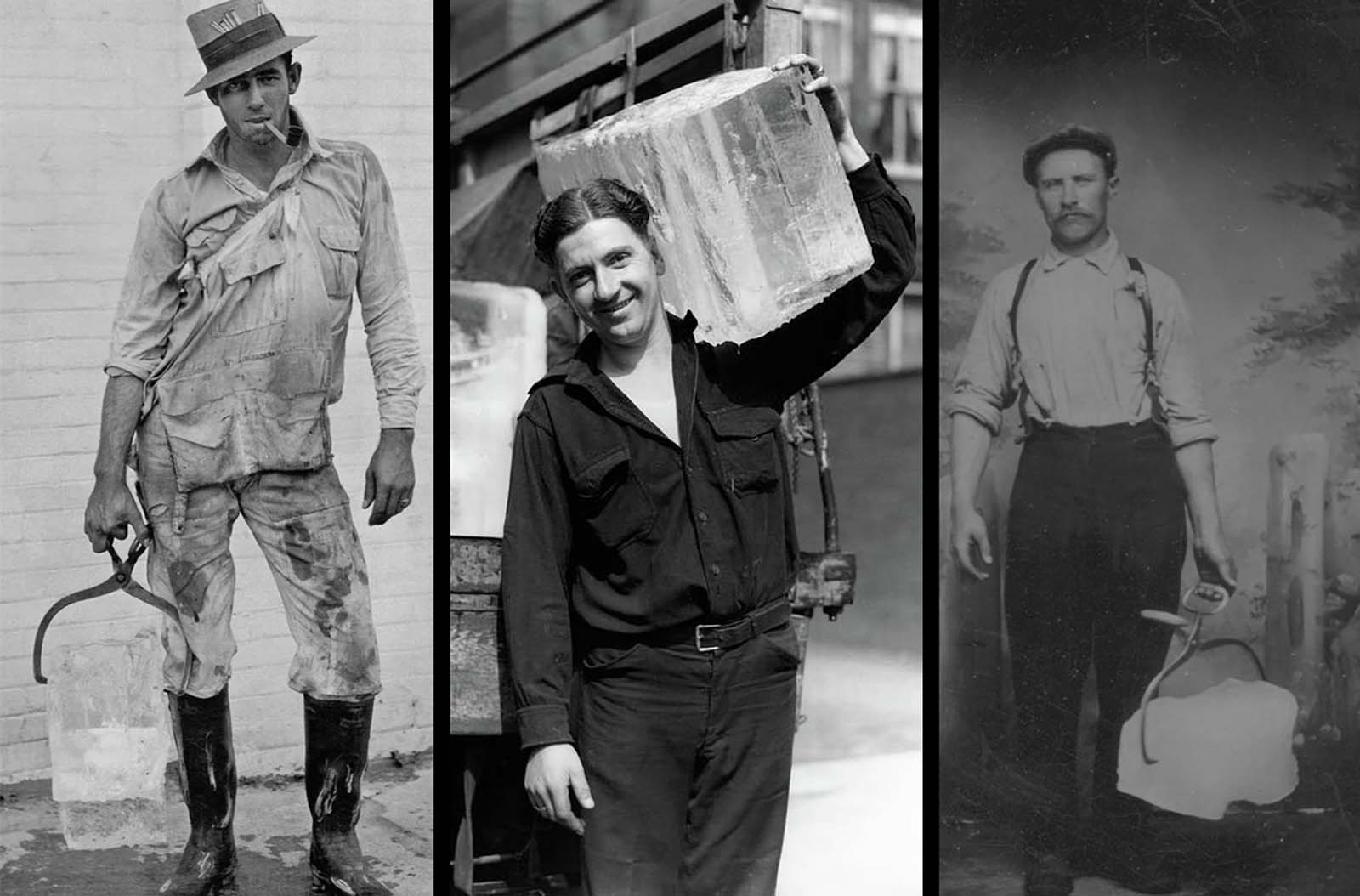

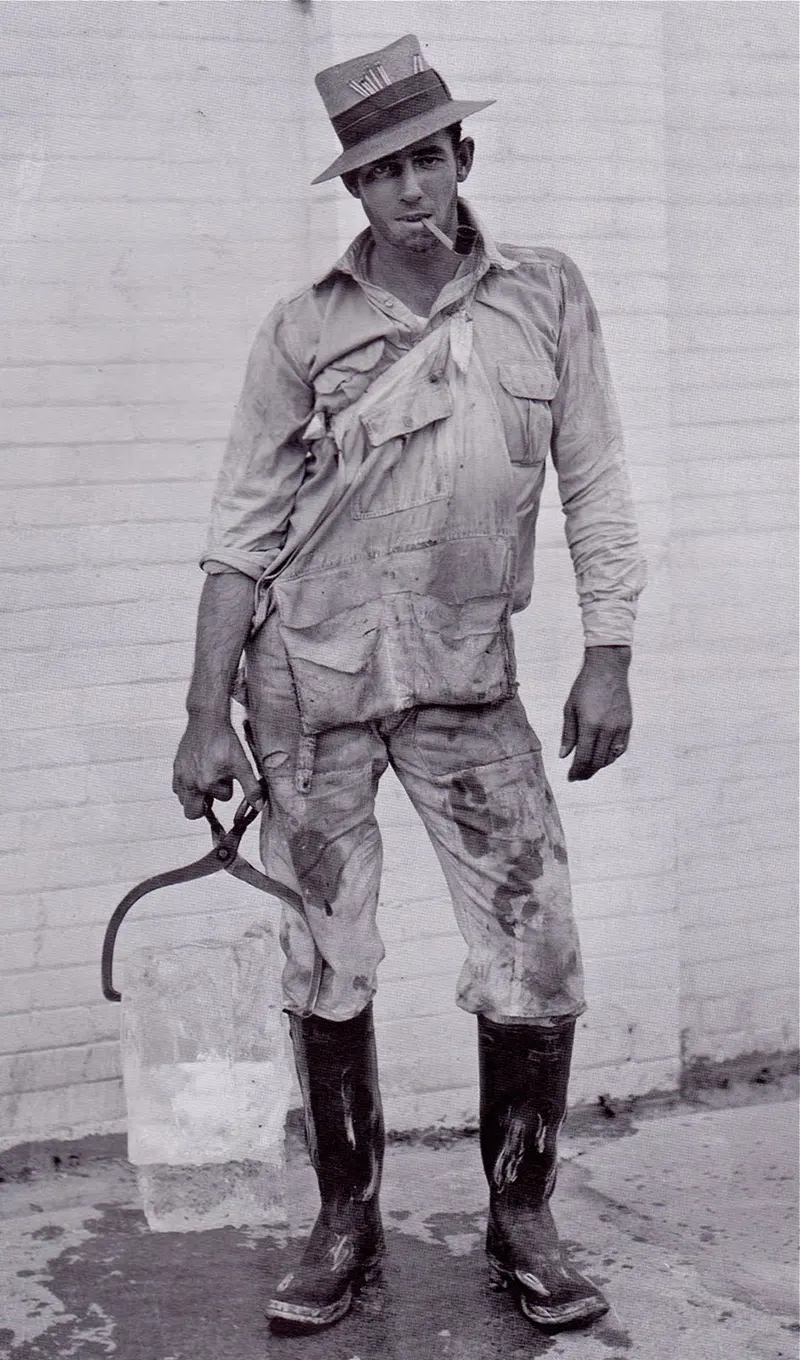

These captivating images offer a glimpse into a past era when the clinking of ice blocks reverberated through the streets, immortalizing the legacy of the icemen and their commitment to providing relief from scorching summers.

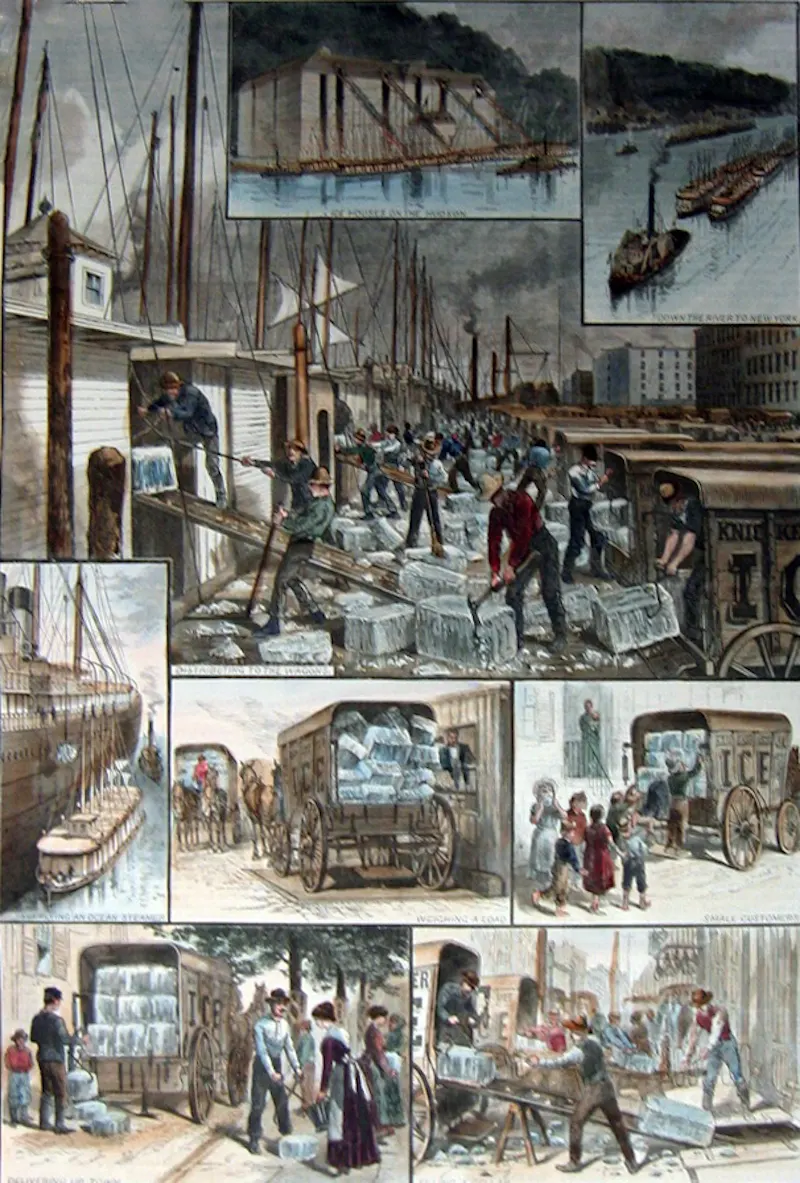

The origins of the ice delivery trade can be traced back to the early 19th century when ice harvesting became a viable industry.

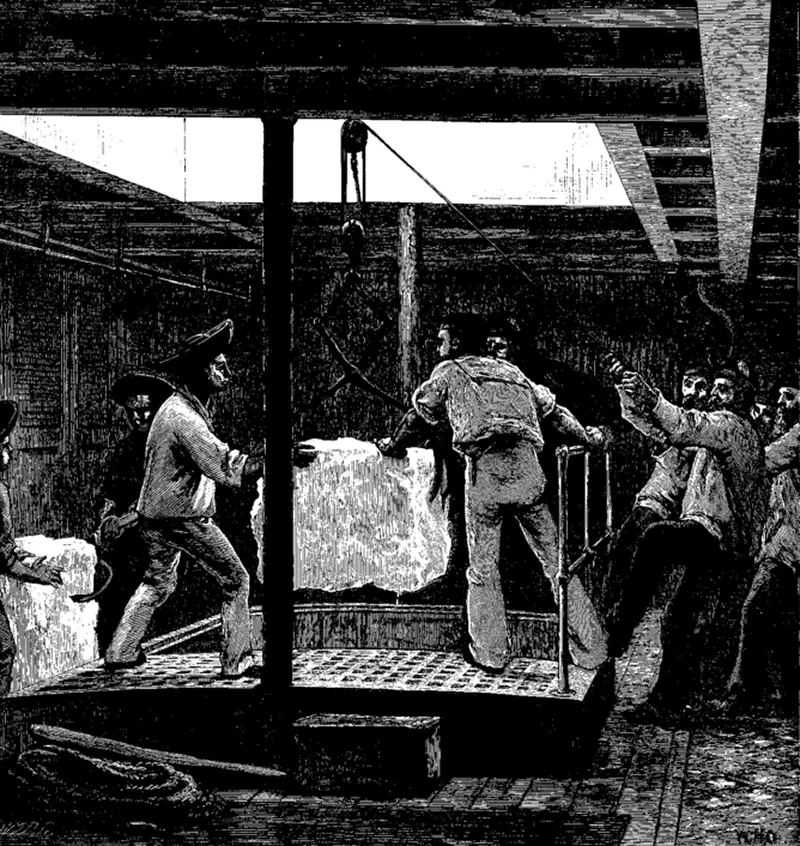

Natural ice was harvested from frozen bodies of water, such as lakes and rivers, during the winter months when the ice was thick enough to support the weight of workers and equipment.

The harvested ice was cut into large blocks and stored in ice houses, insulated structures designed to maintain the ice’s integrity.

An ‘Ice Man’, delivering a 25lb block of ice in 1928, Houston, Texas. Photo from Story Sloane Collection.

The ice blocks were loaded onto horse-drawn or hand-pulled carts, and the icemen set out on their routes, navigating through city streets and rural areas.

They followed predetermined routes, delivering ice to households, restaurants, hotels, and various businesses that relied on this essential commodity.

The icemen’s schedules were often dictated by the natural melting rate of the ice, requiring them to work quickly and efficiently to ensure timely deliveries.

The delivery process was physically demanding. icemen had to handle heavy blocks of ice, often using large ice tongs or hooks to grip and maneuver them.

They would navigate staircases, narrow hallways, and cramped spaces to reach the iceboxes or ice chests where the ice was placed to keep food and beverages cold.

The ice was carefully chipped or sawed into smaller pieces to fit the specific requirements of each customer.

Young women delivering ice, 1918.

Many icemen in the Northeastern U.S. had origins in Southern Italy. Arriving in the U.S. with little education or trade skills, many of these immigrants began ice routes, especially in New York City, where ice routes were a common sight. In those times, ice was harvested from ponds and lakes, stored in ice houses and transported to cities.

As Arthur Miller recalls in his autobiography Timebends, “icemen had leather vests and a wet piece of sackcloth slung over the right shoulder, and once they had slid the ice into the box, they invariably slipped the sacking off and stood there waiting, dripping, for their money.”

An iceman in Germany.

The heyday of the icemen and ice delivery peaked in the late 19th century and early 20th century, with the rise of urbanization and the growing popularity of refrigeration.

The invention of electric refrigerators and the development of mechanical ice-making technology gradually made the delivery of natural ice obsolete.

The occupation of ice delivery lives on through Amish communities, where ice is commonly delivered by truck and used to cool food and other perishables.

Before he became a legendary football player, Harold “Red” Grange worked a summer as an iceman to get in shape.

Ice harvesting generally involved waiting until approximately a foot of ice had built up on the water surface in the winter.

The ice would then be cut with either a handsaw or a powered saw blade into long continuous strips and then cut into large individual blocks for transport by wagon back to the ice house. Because snow on top of the ice slows freezing, it could be scraped off and piled in windrows.

Alternatively, if the temperature is cold enough, a snowy surface could be flooded to produce a thicker layer of ice. A large operation would have a crew of 75 and cut 1500 tons daily.

Before refrigeration, men literally stood on thin ice with saws.

Ice cutting was a considerable export industry for northern countries in Scandinavia and North America during the 19th century.

It started in the United States around 1800, and spread to Scandinavia around 1820, by which Norway by the mid-century became a major exporter to England, Europe, the Mediterranean, and as far away as Kingdom of Kongo, Egypt and New York.

Coastal Telemark had 1,300 workers exporting 125,000 tons in 1895-96, while the Oslo Fjord was the main European export region with Nesodden municipality alone employing 1,000 men and exporting 95,000 tons in 1900, at a time when Norway’s combined ice export at 500,000 tons stood as the world’s largest.

An ice man making a delivery, New York.

However, domestic production and sales were the largest single market source for ice in America and Europe. From the 1850s onwards ice cutting took on large-scale industrial proportions in Germany with Berlin as a key market.

In the 1880s, New York City had over 1500 ice delivery wagons and Americans consumed over 5 million tons of ice annually.

Two icemen make a delivery in Boston.

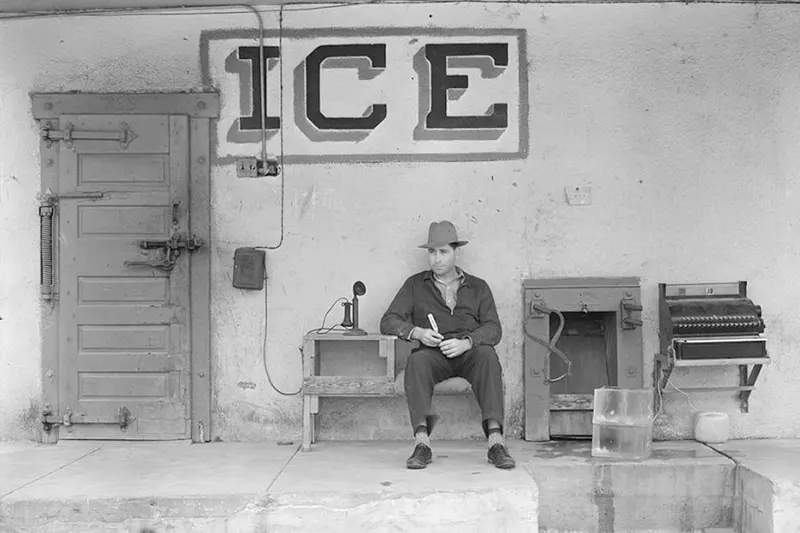

Ice house in Texas, 1939, photographed by Russell Lee.

Men delivering ice in the old days when there were no refrigerators. The Netherlands, 1930s.

Ice delivery in 1930s.

A man lifts a block of ice, using tongs, from an International D-15 truck owned by the Salem Ice Company as he makes a delivery to what appears to be a restaurant.

An iceman delivering his goods in a wagon with an engine, not pulled by horses. Photo: New York Public Library.

The iceman typically delivered to apartments, but this block of ice was left on Mulberry Bend in 1897, in New York.

1940s Crystal Ice delivery truck in Phoenix, AZ. Typically the floor of the truck would be littered with ice chips. This iceman appears to be using something similar to a log carrier rather than the big tongs I saw being used in Oklahoma City.

Iceman and ice-wagon in Crowley, Louisiana, 1938.

Chicago ice wagon ca. 1910.

A photograph that captures the ice cutting process on the Ottauquechee River in 1936.

A photograph that captures the ice cutting process on the Ottauquechee River in 1936.

A photograph that captures the ice cutting process on the Ottauquechee River in 1936.

A photograph that captures the ice cutting process on the Ottauquechee River in 1936.

A photograph that captures the ice cutting process on the Ottauquechee River in 1936.

A photograph that captures the ice cutting process on the Ottauquechee River in 1936.

A photograph that captures the ice cutting process on the Ottauquechee River in 1936.

A photograph that captures the ice cutting process on the Ottauquechee River in 1936.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Flickr / Pinterest / Library of Congress).