Post-First World War aerial photograph of Stonehenge.

Stonehenge, on the Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire in southern England, is certainly one of the most well-known and well-studied prehistoric megalithic monuments.

Scholars had determined that there was a very long process of construction and use of Stonehenge (approximately 3000-1500 BCE), with many additions and alterations made to the site during three distinct phases of building and renovation.

The monument consists of a number of large upright standing stones (menhirs), enclosed within a circular ditch (or henge) with a series of 56 burial pits on the interior of the ditch.

Many archaeologists believe that the stones replaced an earlier timber structure on the site, which served as a type of mortuary chapel for corpses awaiting burial.

The large sarcen (sandstone) menhirs, many of which are still upright today, were set up ca. 2000 BCE and arranged in a circle forming a complete ring with a continuous set of lintel stones.

Farm waggons near the site, c. 1885.

Although there are numerous other examples of prehistoric stone circles (widely distributed throughout the world), Stonehenge is unique in the fact that the builders shaped the huge stones with notches/joints in mortise-and-tenon fashion so that the monumental lintel stones fit nearly into slots carved on the tops of the giant uprights.

Within the sarsen circle are five trilithons (two upright stones sharing a lintel) arranged in a horseshoe shape. The tallest is about 25 feet in height.

In addition, bluestones (so named because they take on a bluish tone when wet) were added in a later phase, and a large altar stone was set up close to the center of the circle.

The bluestones were transported to the site from Wales (about 190 miles away) via water and overland dragging, while the sandstones were dragged to the site from about 15 miles away.

A group of men with a cart in front of Stonehenge. (Photo credit: English Heritage).

Clearly, the efforts entailed to create, maintain, and renovate this monument over thousands of years are evidence that Stonehenge was of extreme significance for the prehistoric peoples of the region.

However, interpretations of the function and purpose of Stonehenge have ranged widely, if not wildly, through centuries of scholarship.

A number of scholars currently agree that Stonehenge primarily, if not originally, served as a monumental observatory for charting the seasons of the year by indicating the summer and winter solstices. The midsummer sun rises over a specific stone, and several stones are also aligned to the midwinter sunset.

The archaeo-astronomical aspect of Stonehenge has attracted the greatest attention in late 20th-century technology-based scholarship, although other theories about Stonehenge (as a site of ancient Druid rituals, as a marker of territory, as a solar temple for the worship of the sun God) have been proposed.

This horse and carriage image was shared with English Heritage by the descendants of Isabel, Maud, and Robert Routh who can be seen in the photograph.

The modern story of restorations at Stonehenge begins in 1880 when the site was surveyed by William Flinders-Petrie, who also established the numbering system for the stones that is in use to this day.

The very first documented intervention to prevent stone collapse at Stonehenge happened in 1881 by Simon Banton. In 1893, the Inspector of Ancient Monuments determined that several stones were in danger of falling and he was subsequently proved correct when stone 22 collapsed in a New Year’s Eve storm on 31 December 1900.

William Gowland oversaw the first major restoration of the monument in 1901, which involved the straightening and concrete setting of sarsen stone number 56 which was in danger of falling. In straightening the stone he moved it about half a meter from its original position.

Gowland also took the opportunity to further excavate the monument in what was the most scientific dig to date, revealing more about the erection of the stones than the previous 100 years of work had done.

During the 1920 restoration William Hawley, who had excavated nearby Old Sarum, excavated the base of six stones and the outer ditch. He also located a bottle of port in the Slaughter Stone socket left by Cunnington, helped to rediscover Aubrey’s pits inside the bank, and located the concentric circular holes outside the Sarsen Circle called the Y and Z Holes.

Richard Atkinson, Stuart Piggott, and John F. S. Stone re-excavated much of Hawley’s work in the 1940s and 1950s and discovered the carved axes and daggers on the Sarsen Stones. Atkinson’s work was instrumental in furthering the understanding of the three major phases of the monument’s construction.

In 1958 the stones were restored again when three of the standing sarsens were re-erected and set in concrete bases. The last restoration was carried out in 1963 after stone 23 of the Sarsen Circle fell over. It was again re-erected, and the opportunity was taken to concrete three more stones.

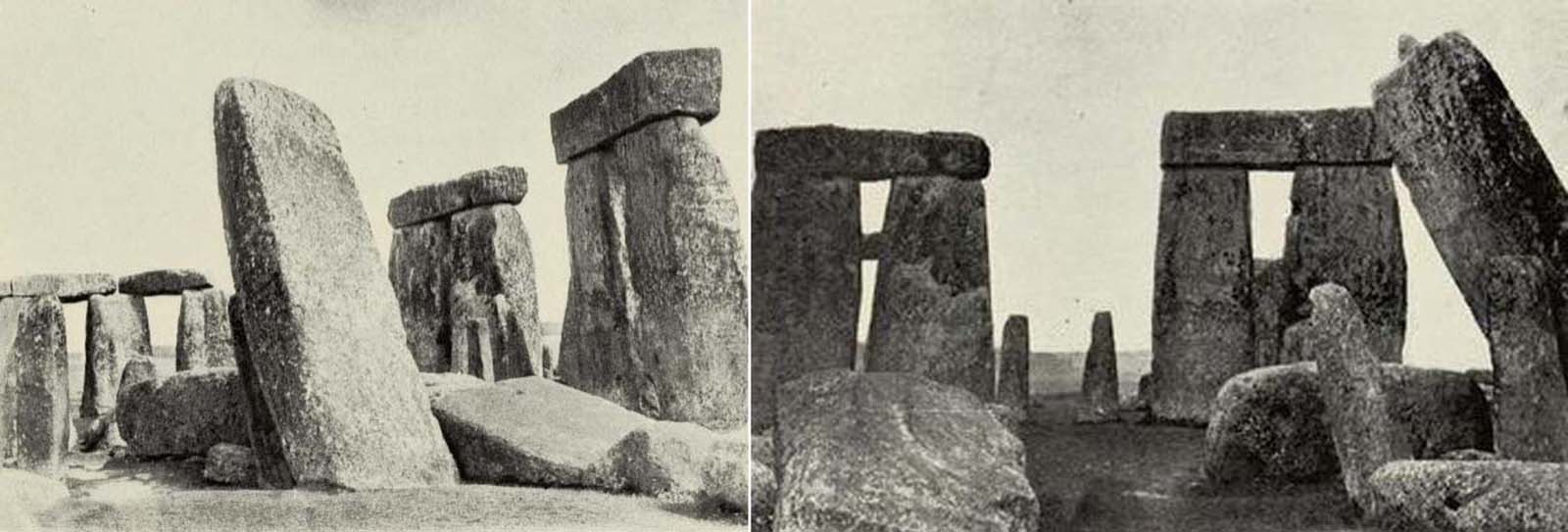

Before and after restoration. 1901.

Later archaeologists, including Christopher Chippindale of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge and Brian Edwards of the University of the West of England, campaigned to give the public more knowledge of the various restorations and in 2004 English Heritage included pictures of the work in progress in its book Stonehenge: A History in Photographs.

As with other examples of architectural forms from prehistory, the lack of written records makes it difficult to do anything other than purely speculate about the purpose and function.

The logical tendency is to assume that Stonehenge had a religious or ritual function of some sort, but the exact nature of this will doubtless continue to be explored by generations of scholars and enthusiasts of the future.

Sarsen mauls and flint hammerstones excavated during the restorations.

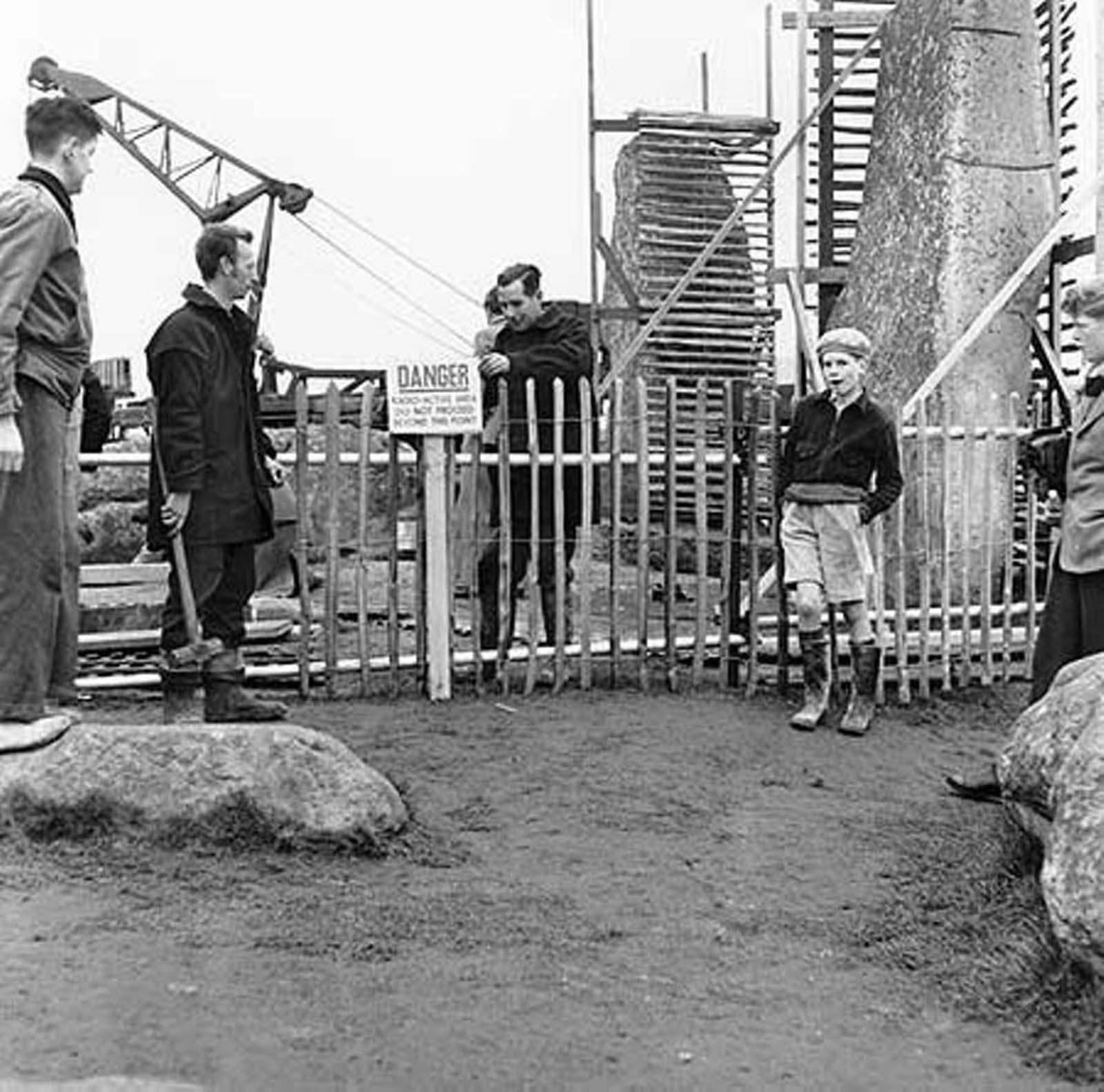

Restorations on Stonehenge. 1958.

Restorations on Stonehenge. 1958.

Restorations on Stonehenge. 1958.

Lifting Bluestone 36 with block and tackle.

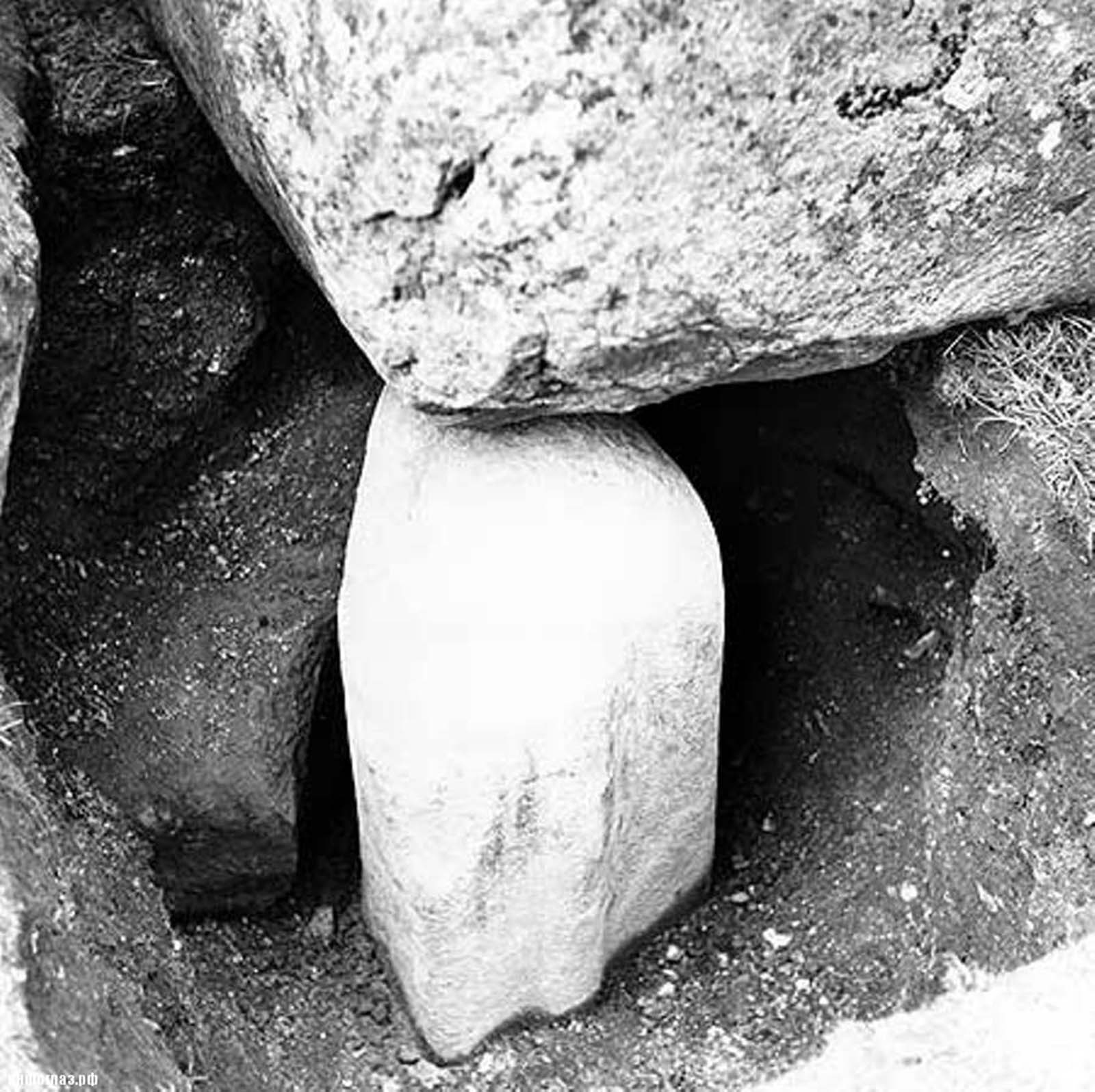

Bluestone lintel 36 being cleaned after excavation. The presence of finely tooled mortices indicates that it was re-used from an earlier bluestone Trilithon. 1954. (Photo credit: Historic England Archive).

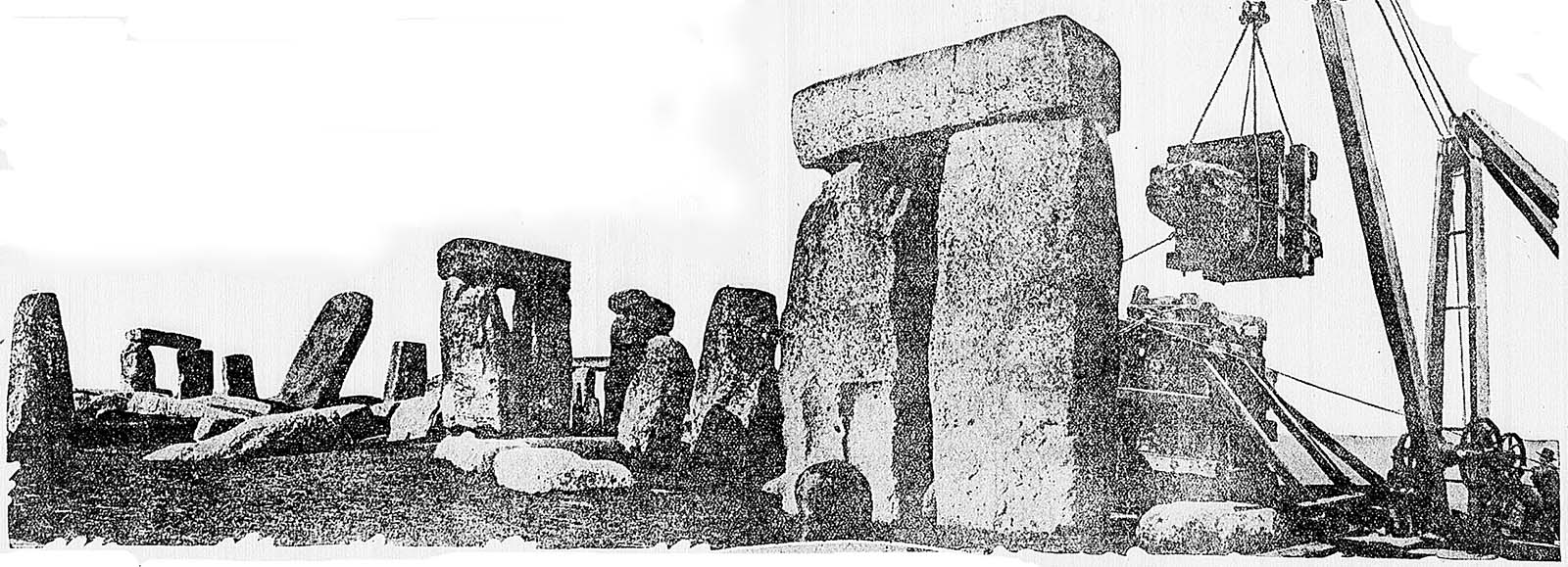

Lintel 158 is hoisted into position on top of the restored west trilithon.

Lintel 158 is hoisted onto its perch atop the restored west trilithon. The borrowed RAF ‘Babarazon aircraft crane could lift up to 60 tons — approaching its limits with the huge stone uprights.

During the spring of 1958 the whole area was screened down with timbers in a herringbone fashion to the chalk, to prevent the heavy machinery damaging the fragile ground surface. With the west trilithon stones to be re-erected having previously been lifted aside, a broad swath of ground is clearly visible in this photograph.

Mr T. A. Bailey, senior engineer, examining the lintels over stones 19, 20 and 1 of the outer circle. These stones were not moved by (Professor) Atkinson but had been straightened by Professor Hawley in 1920. These stones mark the entrance to Stonehenge. The archaeologist Stuart Piggott can also be seen in the photograph, on his knees smoking a pipe. (Photo credit: Historic England Archive).

A contemporary newspaper depiction of the 1920 restoration.

Bluestone 66, excavated in 1953. This spotted dolerite bluestone 66 is now a ground-level stump underneath the southern corner of fallen Stone 55b.

Periglacial stripes of the upper Avenue looking east. These gullies created by ice or meltwater may have played a part in the original decision to position Stonehenge at this location.

Cuttings C41 and C42 across Segment 98 of the henge ditch. Two antlers found at the bottom of C42 (seen in this image) gave calibrated radiocarbon dates of 3340-2910 cal BC. (Photo credit: Historic England Archive).

A site meeting, Professor Atkinson is in the foreground here, seated to the right.

Stone 23 of the outer sarsen circle, which collapsed in December 1900, being lifted prior to its re-erection. (Photo credit: Historic England Archive).

Bluestone 69 of the Bluestone Horseshoe being removed to allow a crane access to lift fallen Trilithon stones 57 and 58. This stone was replaced after the re-erection of the Trilithon. 1958. (Photo credit: Historic England Archive).

Restoration on Stonehenge. 1958.

Moving stone 22. 1958.

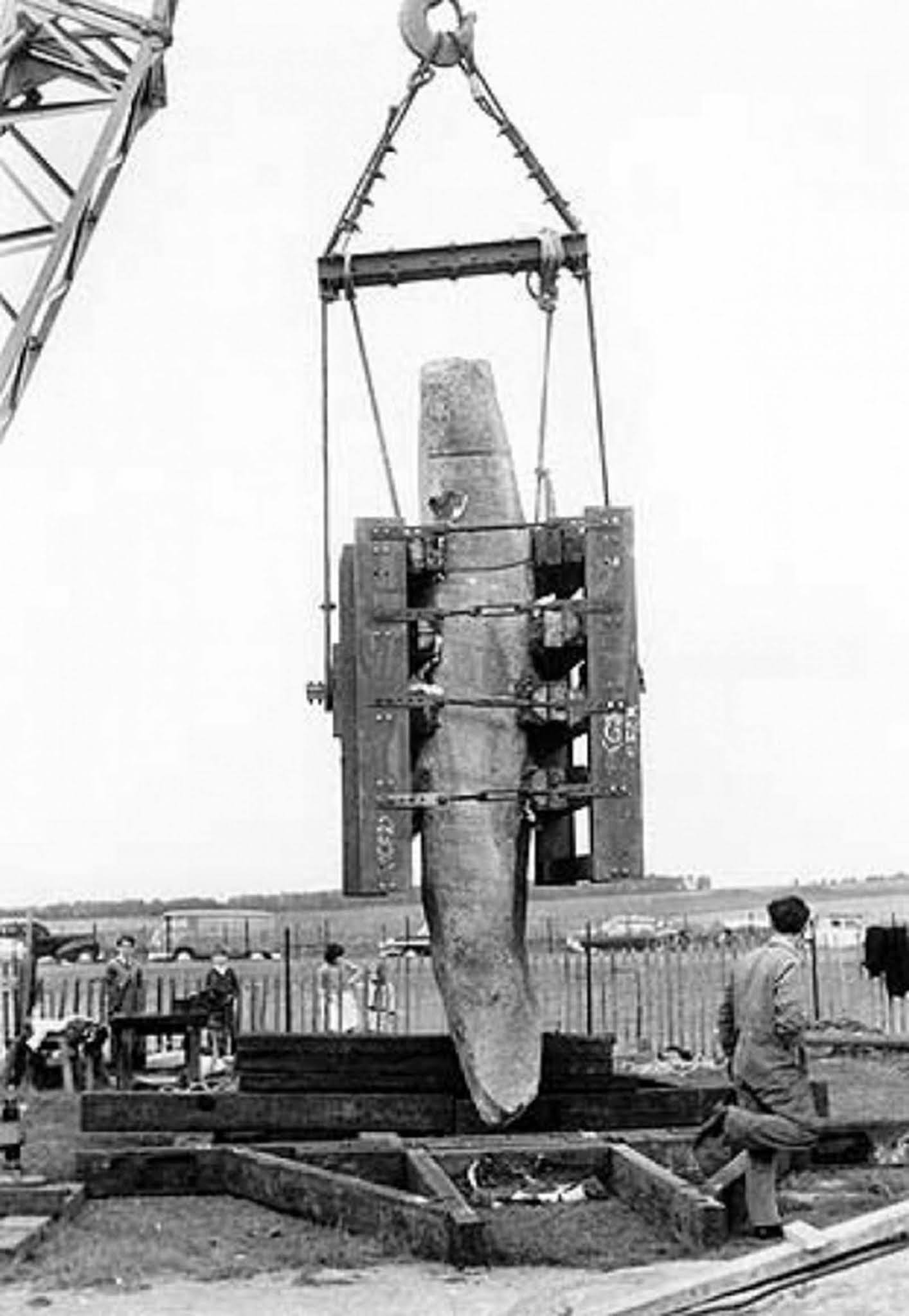

The top of sarsen stone 23, showing two tenons to secure lintels. The stone collapsed in 1964 and was re-erected by Professor Atkinson in 1964. Encased here in a protective cradle, ready for re-erection.

Moving stone 22 in 1958.

Professor Richard Atkinson and another archaeologist remove one of the stones used as packing for the uprights of the outer sarsen circle. (Phot credit: Historic England Archive).

Mr T. A. Bailey, Senior Engineer, measuring the inclination of stone 54.

Checking stone 56.

One of the early photographs of Stonehenge.

Richard Atkinson (in the trench, second from right) and team excavating the bluestone circle in 1954.

Restoration on Stonehenge.

A lintel of the outer circle is lifted into place in 1958.

(Photo credit: Historic England Archive / Austin Kinsley from Restorations at Stonehenge / Library of Congress / Wiki Commons).